Human Cloning: What the Records Show—and Where They Stop

What can the surviving institutional record certify about human cloning mechanics and debates, and what can it no longer certify about cloned human births?

This case turns on a narrow problem: separating what the documents here define and discuss from what they do not verify.

- Corporate PDF claim of cloned human embryos for research, not a birth

- U.S. Senate hearing text as a formal record of cloning debate

- House committee report using medical risk framing for prohibition rationale

- Prominent cloning-related claims later investigated and discredited

- No Tier-1 proof of a verified cloned human birth in this validated set

These points define the stable edge of certification in the provided archive, and the record does not stabilize beyond them.

Evidence gate: the NHGRI Cloning Fact Sheet as the baseline document for what cloning means

A federal genomics institute maintains a public fact sheet under a simple title: Cloning Fact Sheet. The administrative act is publication and upkeep of a definitional page, not a case report.

The page separates several biomedical uses of the term cloning. It keeps gene or DNA cloning distinct from reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning.

Within the reproductive cloning context, the fact sheet describes somatic cell nuclear transfer at a high level. It presents nucleus transfer into an egg cell that has had its nucleus removed.

The description ties the resulting embryo to the nucleus donor through genetics, without equating that link to an individual life. The page stays inside technique framing rather than outcome documentation.

No medical record, regulator finding, or chain-of-custody genetic test appears as part of the fact sheet. The artifact functions as terminology control, not event verification.

The document remains accessible as a stable reference point for category separation and for the SCNT mechanism label used in reproductive cloning discussions.[1]

This evidence gate can certify how this archive uses the word cloning and which mechanism label anchors reproductive cloning talk. It cannot certify any brought-to-term human cloning outcome. The next question is what other artifacts actually claim.

The Stemagen press document and the hard boundary between embryo claims and birth claims

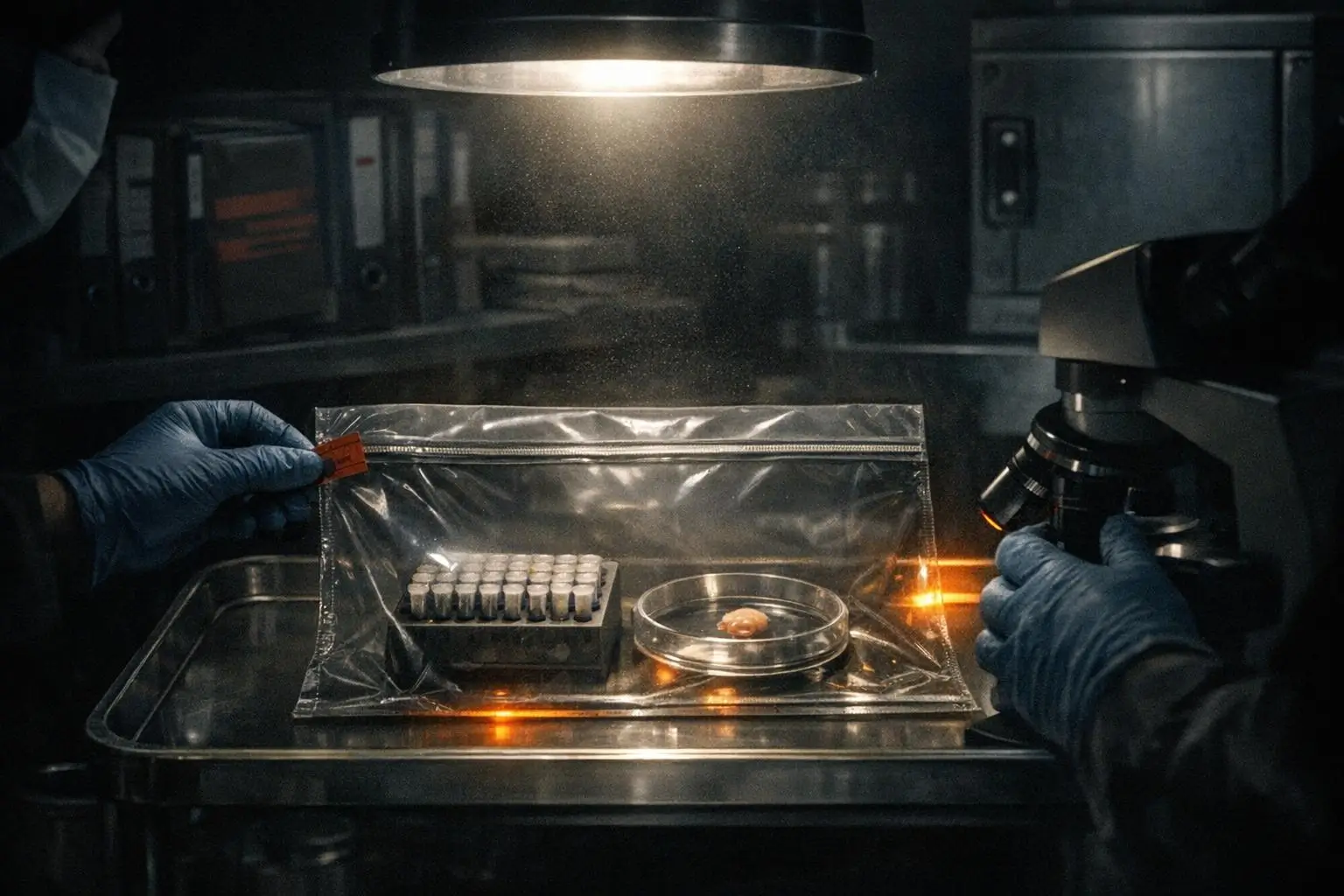

A corporate press document asserts creation of cloned human embryos for research purposes. The artifact is a PDF, which means its primary certified content is what the issuer chose to publish, not what an external auditor verified.

Inside this validated set, that claim stays in the embryo category. It does not become a claim of a cloned human being brought to term. The archive does not supply accompanying medical files, regulator determinations, or independently audited genetic testing tied to any birth.

What remains unresolved is not a theory about secrecy. It is the absence, here, of the specific verification trail required to evaluate any escalation from embryo creation to a live birth claim.[2]

The Senate hearing record: what a formal institutional transcript can and cannot do

The U.S. Congress preserves a full-text hearing record titled S. Hrg. 107-1050 on human cloning. The transcript reads as an institutional artifact, with structured sections and preserved proceedings rather than experimental data.

Within this archive, the hearing can certify that arguments about prohibiting human cloning were made on record, including stated concerns about risks and feasibility. It cannot certify that any party had already produced a verified cloned human birth. Debate and framing do not substitute for proof of an event.

The unresolved next step is whether the legislative record contains a tighter rationale document connecting prohibition language to specific risk claims.[3]

The House committee report: risk framing written into prohibition rationale

A House committee report for the Human Cloning Prohibition Act of 2003 connects attempts to clone human beings with substantial medical risks. In this set, that linkage is certified as a documented rationale used to support prohibition legislation.

The same document does not operate as a laboratory record or a clinical registry. Its certified function is legislative framing. It does not settle whether any attempt succeeded, where it happened, or whether any claimed birth was independently tested.

The next unresolved question is how much of the feasibility and obstacle discussion in the broader cloning era can be anchored to dated institutional secondary records, without drifting into claims of outcomes.[4]

After Dolly the sheep: institutional secondary records that shaped feasibility talk

An institutional secondary record from MIT News captures early post-Dolly discussion about cloning as a public scientific milestone with obstacles still in view. Within this archive, it serves as a dated context artifact, not a confirmation of human reproductive cloning.[5]

A museum narrative about Dolly the sheep preserves a public-facing account of the animal case. It can certify that Dolly sits in the documented background of later cloning debates. It does not certify anything about human births or secret laboratory activity in this validated set.[6]

The Hwang Woo-suk record: a documented discrediting that tightens the verification standard

The archive contains a specific example where prominent cloning-related claims were investigated and further discredited in the surviving record. This functions as a procedural constraint: publicity is not verification when later scrutiny undermines the claim.[7]

A companion archival trace exists in PubMed Central, reinforcing that this was not merely an informal dispute in commentary space. It documents that the claim domain has a history where formal investigation mattered, and where the public narrative changed after review.[8]

This does not certify that other cloning allegations are false. It certifies that the bar for accepting a human cloning outcome claim must include independent, auditable documentation, which this set does not provide for any verified cloned human birth.

A copied genome is not a copied person: the boundary that blocks identity drift

A peer-reviewed source in PNAS frames the difference between copying a genome and recreating an individual. In this archive, that framing blocks a common slide in language where genetic similarity is treated as personal duplication.[9]

This boundary does not answer whether any secret laboratory exists. It is not an investigative finding about a specific site. It does define what the archive can say even if a genetic match were documented: DNA identity alone would not certify the recreation of an individual life.

Where the record stops on secret-lab human clones, and what documents would be needed to move it

The validated archive can certify controlled definitions of cloning, including category separation and the SCNT label as a reproductive cloning mechanism reference point. It can also certify that formal U.S. congressional records preserved debate and risk-based prohibition rationale.

The same archive can certify that an issuer-published corporate document claimed cloned human embryos for research, and that this claim is distinct from any claim of a cloned human birth. It can also certify a prominent verification failure case where later investigation discredited high-profile claims.

What it cannot certify is the central event implied by secret-lab narratives: a verified human reproductive clone brought to term. The stopping point is concrete in this set. There are no medical records, no court filings, no regulator findings, and no independently audited genetic testing reports tied to a specific birth claim.

Because those categories of documentation are absent here, allegations often associated in public talk with hidden labs, Clonaid, or the Raëlian movement remain unresolved inside this archive. The record preserves the allegation space only as a gap, not as a certified event trail.

To move beyond this stopping point, the future archive vector would need regulator or inspector findings, court-tested documentation, and chain-of-custody DNA testing tied to a specific claim. None of these is present in the validated set.[1]

FAQs (Decoded)

Does this archive confirm that a cloned human being has been born?

No. The validated set does not include Tier-1 primary proof of a verified cloned human birth, and it does not include auditable medical or genetic documentation tied to such a claim. Source: National Human Genome Research Institute, Cloning Fact Sheet.

What does cloning mean in the documents used here?

The NHGRI fact sheet separates different biomedical uses of cloning, including gene or DNA cloning, reproductive cloning, and therapeutic cloning, and the article keeps those categories apart. Source: National Human Genome Research Institute, Cloning Fact Sheet.

What mechanism is used as the reference point for reproductive cloning talk?

The archive uses somatic cell nuclear transfer as the named technique reference point, as described at a high level in the NHGRI fact sheet. Source: National Human Genome Research Institute, Cloning Fact Sheet.

Do congressional hearings and reports prove that human cloning was achieved?

No. In this archive they certify what was debated and how risks and feasibility were framed on record, not that a verified event occurred. Source: U.S. Congress, S. Hrg. 107-1050 and committee report records.

Do embryo-cloning-for-research claims equal a claim of a cloned human birth?

No. The corporate document in this set is treated as an embryo claim artifact, and the archive does not supply the extra documentation required to treat it as a birth claim. Source: Stemagen, press document PDF.

Why does the Hwang Woo-suk case matter in this context?

It is a documented example where prominent cloning-related claims were later discredited after investigation, reinforcing that independent verification is necessary for high-salience claims. Source: Science (AAAS), discrediting coverage.

For related documentation on biomedical boundary cases, see the forbidden science archive, the controversial medical files, the crispr babies case files, and the human-animal hybrid research files.

Sources Consulted

- National Human Genome Research Institute, Cloning Fact Sheet. genome.gov, accessed 2025-02-07

- Stemagen, press document PDF. stemagen.com, accessed 2025-01-31

- U.S. Congress, S. Hrg. 107-1050 full text. congress.gov, accessed 2025-01-24

- U.S. Congress, H. Rept. 108-18 committee report text. congress.gov, accessed 2025-01-17

- MIT News, Cloning coverage page. news.mit.edu, accessed 2025-01-10

- National Museums Scotland, The story of Dolly the sheep. nms.ac.uk, accessed 2025-01-03

- Science (AAAS), Hwang’s stem cell claims further discredited. science.org, accessed 2024-12-27

- PubMed Central, archived article record. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed 2024-12-20

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Cloning humans? Biological, ethical, and social considerations. pnas.org, accessed 2024-12-13

A Living Archive

This project is never complete. History is a fluid signal, often distorted by those who record it. We are constantly updating these files as new information is declassified or discovered.